Extensive research has shown the potential value of digital health solutions and highlighted the importance of clinicians’ adoption. As general practitioners (GPs) are patients’ first point of contact, understanding influencing factors to their digital health adoption is especially important to derive personalized practical recommendations. Using a mixed-methods approach, this study broadly identifies adoption barriers and potential improvement strategies in general practices, including the impact of GPs’ inherent characteristics – especially their personality – on digital health adoption. Results of our online survey with 216 GPs reveal moderate overall barriers on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with required workflow adjustments (M = 4.13, SD = 0.93), inadequate reimbursement (M = 4.02, SD = 1.02), and high training effort (M = 3.87, SD = 1.01) as substantial barriers. Improvement strategies are considered important overall, with respondents especially wishing for improved interoperability (M = 4.38, SD = 0.81), continued technical support (M = 4.33, SD = 0.91), and improved usability (M = 4.20, SD = 0.88). In our regression model, practice-related characteristics, the expected future digital health usage, GPs’ digital affinity, several personality traits, and digital maturity are significant predictors of the perceived strength of barriers. For the perceived importance of improvement strategies, only demographics and usage-related variables are significant predictors. This study provides strong evidence for the impact of GPs’ inherent characteristics on barriers and improvement strategies. Our findings highlight the need for comprehensive approaches integrating personal and emotional elements to make digitization in practices more engaging, tangible, and applicable.

In the contemporary healthcare landscape, digital technologies have emerged as powerful tools, offering the potential to improve health outcomes 1,2 , reduce costs 3 , enhance patient care 4,5 , and improve the effectiveness and efficiency of healthcare delivery 3,6,7 . This spread of digital health solutions was further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic 8 . Despite the potential benefits of digital health solutions, their adoption and successful integration into healthcare organizations has been slow 9,10 and impeded by various barriers 11,12 . As the digitalization of healthcare continues to reshape medical practices, understanding and addressing perceived barriers among general practitioners (GPs) is paramount. In this context, extensive research has studied digital health adoption across various medical disciplines, healthcare settings, and technologies, ranging from remote consultations 13,14 to mHealth 15,16 , electronic medical records 17,18 , and remote monitoring 19,20 . Today, only a few studies considered a broader perspective on digital health adoption 21 , investigated potential strategies to improve adoption 22,23 , and studied potential influencing factors 24 .

Amid the digitalization of healthcare, GPs can choose various digital health solutions for their practice, ranging from video consultations and mobile health apps to digital appointment booking. As GPs are most patients’ primary point of contact 25 in European healthcare systems, they are thus at the center of providing comprehensive and continuous healthcare services 26 . Consequently, GPs’ adoption and effective utilization of digital health solutions significantly impact the integration of these technologies into routine clinical practice 12 and, hence, influence patient care. Moreover, GPs’ adoption of digital health solutions can enhance their job satisfaction and work-life balance 27 .

Therefore, understanding factors influencing the barriers perceived among GPs is vital to fostering the effective and sustainable adoption of digital health solutions in a rapidly evolving landscape. By digital health solutions, in this study, we mean digital tools, technologies, and services designed to improve healthcare, make it more efficient, and personalize it. This includes the use of digital services (e.g., video consultations, digital telephone assistance system, digital appointment booking, digital medical history, digital practice administration) and the use of connected medical devices and artificial intelligence (e.g., telemonitoring, decision support systems).

Through a mixed-methods research approach combining qualitative (i.e., literature review, expert interviews) and quantitative methodologies (i.e., online survey), we aim to identify adoption barriers and potential strategies for improvement in general practice settings more broadly and further evaluate their association with GPs’ inherent characteristics, especially their personality. As the research on influencing factors to digital health adoption in general practices is limited, we close this gap by providing a more nuanced understanding of inherent characteristics and their effect on digital health adoption among GPs. Understanding these inherent influencing factors enables the development of evidence-based, targeted strategies to address resistance and facilitate the successful integration of digital health solutions into clinical practice, whether through communication styles that resonate with different personality types or by providing additional support to individuals less comfortable with technological change. Tailoring interventions to the specific needs and characteristics of GPs enhances the effectiveness of digital health adoption strategies.

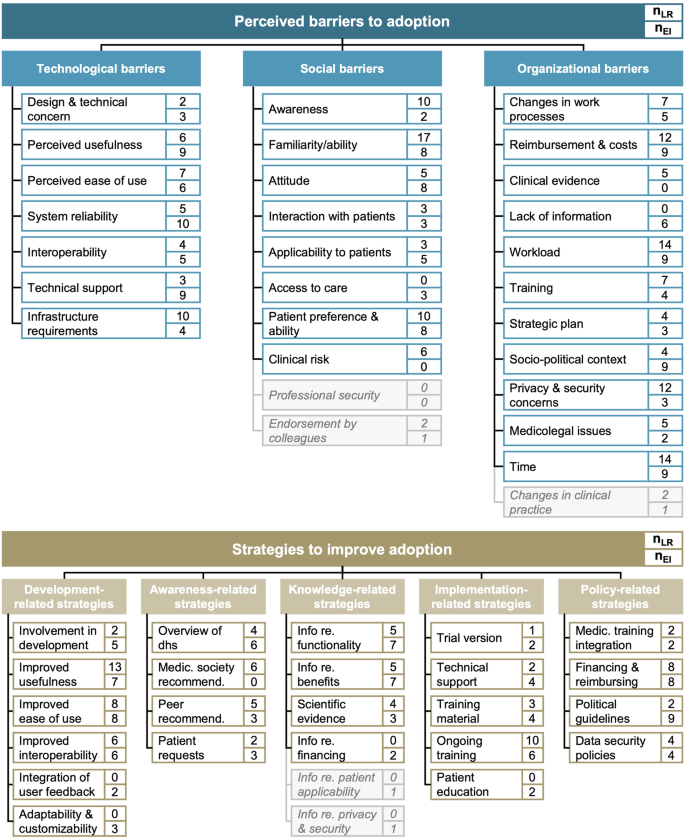

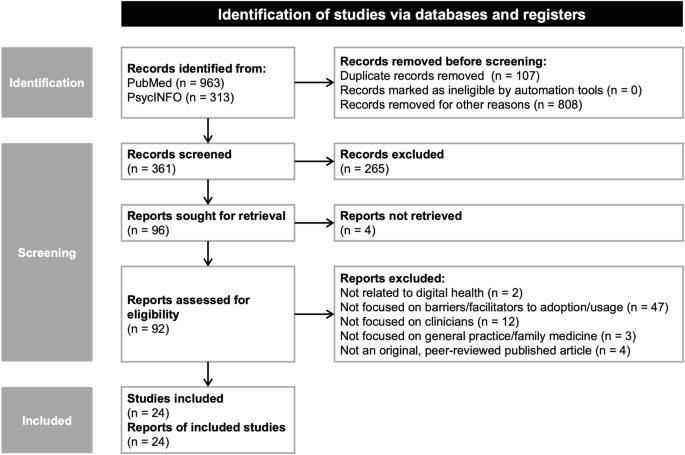

Our literature review and expert interviews aimed to identify and synthesize currently postulated adoption barriers and improvement strategies for digital health adoption more broadly and validate their relevance in general practice settings. We initially retrieved 1276 records in the literature search, of which we included 24 articles 13,15,17,18,19,22,23,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 .

The literature review identified technological, social, and organizational adoption barriers. More than 90% of included studies reported organizational adoption barriers 13,15,17,18,22,23,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 (23/24), with more than half reporting high workload 17,22,29,30,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 and a lack of time 13,15,17,18,23,28,29,31,32,33,34,36,40,42 (each 14/24; 58%) as predominant barriers. Another 88% of studies identified social adoption barriers 13,15,17,18,22,23,28,29,30,31,32,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 (21/24). Of these, physicians’ familiarity with digital health solutions 15,17,18,22,23,28,30,31,32,36,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 (17/24; 71%) was the most cited social barrier, followed by overall awareness 15,18,22,23,29,30,32,35,43,44 (10/24; 42%) and patient preferences 15,18,23,29,30,31,35,38,40,42 (10/24; 42%).

Our ten expert interviews with GPs confirmed and validated the relevance of all three categories of barriers and five categories of improvement strategy. Overall, the relevance of the three categories of barriers was consistently rated as high. In line with the high estimated relevance, all GPs mentioned technological barriers, especially regarding system reliability (10/10; 100%), usefulness (9/10; 90%), and technical support (9/10; 90%). Additionally, most GPs mentioned the familiarity and ability of practice staff (each 8/10; 80%), patients’ preferences and ability (8/10; 80%), a lack of reimbursement (9/10; 90%), a high workload and lack of time (each 9/10; 90%), and the socio-political context (9/10; 90%) as substantial adoption barriers. On average, GPs reported around 14 different barriers.

Looking into potential strategies to support and improve digital health adoption, we identified strategies in five categories in our literature review: development-related, awareness-related, knowledge-related, implementation-related, and policy-related strategies. Around two-thirds of studies identified strategies concerning the development of digital health solutions as potentially helpful to improve adoption 15,17,18,19,28,29,31,33,34,36,37,38,39,42,43,44 (16/24; 67%). Among these, the most frequently cited development-related strategies were improvements in the usefulness of digital health solutions 17,18,19,28,29,31,33,36,37,38,42,43,44 (13/24; 54%), followed by improvements in their usability 28,29,31,34,36,39,42,43 (8/24; 33%). All other categories were present in around half of the included studies, with the call for ongoing training 15,17,18,19,34,37,38,40,43,44 (10/24; 42%) and improved reimbursement 15,17,18,22,34,38,39,43 (8/24; 33%) as additionally vital improvement strategies.

Our expert interviews further highlighted that GPs considered development-related strategies particularly relevant: 80% of GPs would like to see improved usability of digital health solutions (8/10). In addition, GPs especially called for improvements in remuneration (8/10; 80%) and a simplification of political guidelines (9/10; 90%). Awareness-related strategies were rated as least relevant (6.2/10.0). Of these, GPs wished for further information on the functionalities and benefits of digital health solutions (each 7/10; 70%). Overall, GPs reported around 11 strategies. In our subsequent online survey, we only included items for barriers or strategies proposed by more than four articles or mentioned by more than one interviewee to ensure theoretical and expert consensus. Figure 1 shows the synthesized results.

To analyze factors that may influence adoption barriers and improvement strategies, our online survey focused on five areas of inherent characteristics: (i) demographics and practice-related characteristics, (ii) digital health usage, (iii) digital affinity, (iv) personality, and (v) digital maturity of the practice.

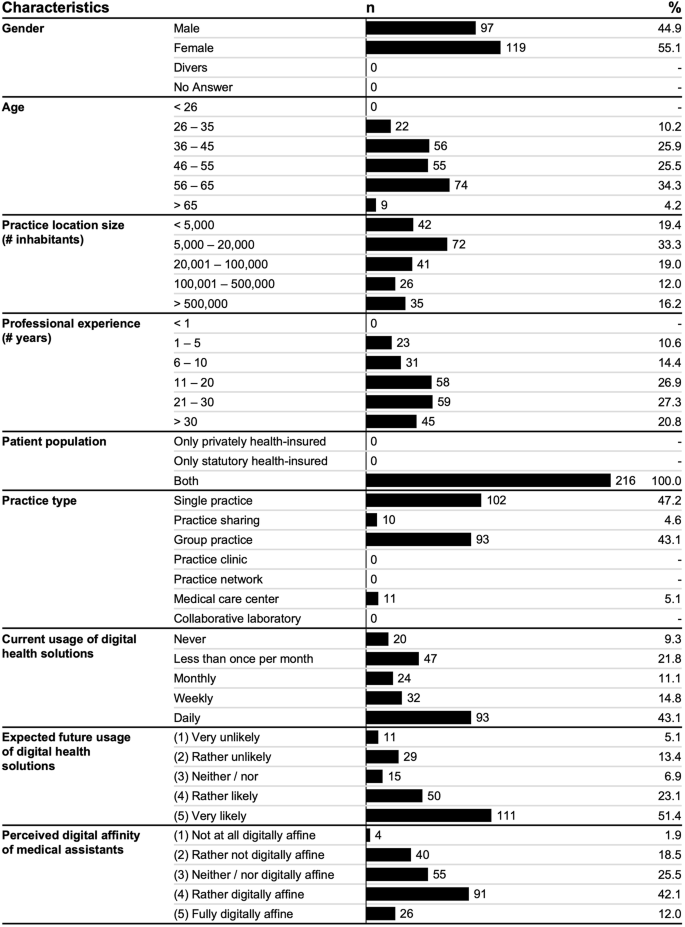

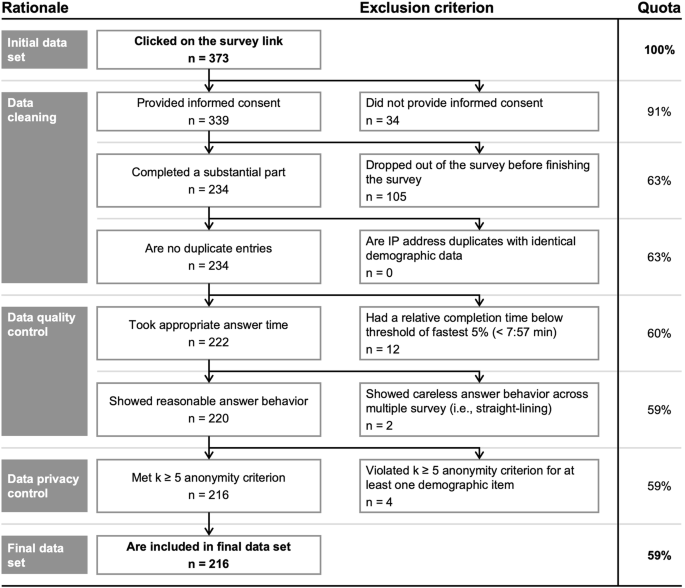

After data cleaning, quality, and privacy control, we included a broad sample of 216 German GPs with a diverse set of demographics (see Fig. 2).

Around half of respondents used digital health solutions daily (93/216; 43.1%), while almost a third did not use them at all (20/216; 9.3%) or rather seldomly (47/216; 21.8%). Most respondents further expected to rather or very likely use digital health solutions in the future (161/216; 74.5%).

Further, GPs perceived the work-related digital affinity of their medical assistants to be moderate (55/216; 25.5%) or relatively high (91/216; 42.1%) and had a relatively moderate affinity for technology interaction 45 themselves (M = 2.66, SD = 1.08).

Concerning personality 46 , respondents can be characterized as highly conscientious (M = 4.10, SD = 0.59) and open (M = 3.85, SD = 0.68), moderately extroverted (M = 3.64, SD = 0.80) and agreeable (M = 3.53, SD = 0.75), and mildly neurotic (M = 2.42, SD = 0.71). The digital maturity of their practices was moderate (M = 3.32, SD = 0.64).

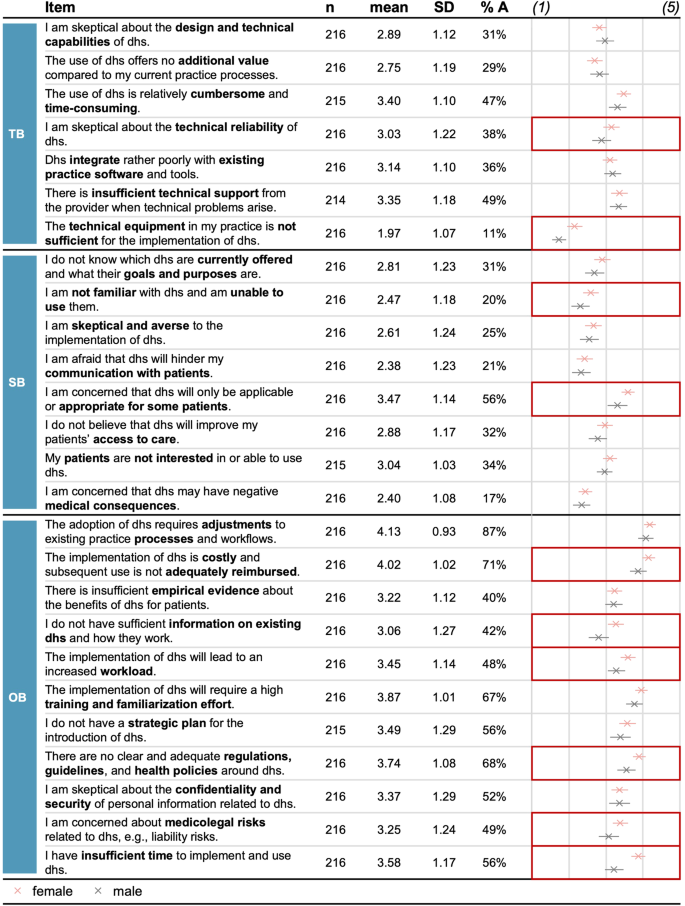

Overall, respondents saw around 11 barriers (M = 11.12, SD = 6.01) and rated these as relatively moderate (M = 3.08, SD = 0.68). Among the three categories, organizational barriers were rated highest on average (M = 3.56, SD = 0.71), followed by technological (M = 2.93, SD = 0.76) and social (M = 2.76, SD = 0.79) barriers. For most individual barriers, scores were again moderate, with the highest rating for required workflow adjustments (M = 4.13, SD = 0.93), high costs and inadequate reimbursement (M = 4.02, SD = 1.02), and a high training and familiarization effort (M = 3.87, SD = 1.01) as the top three barriers (see Fig. 3).

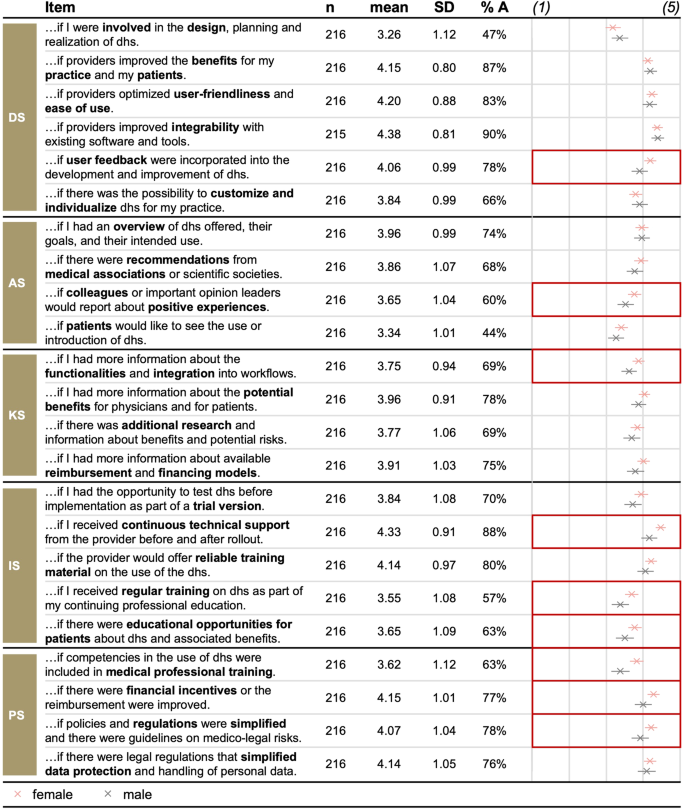

On average, respondents perceived around 16 improvement strategies as important (M = 3.89, SD = 0.61). Policy-related (M = 4.00, SD = 0.81) and development-related strategies (M = 3.98, SD = 0.67) received the highest rating, followed by implementation-related (M = 3.90, SD = 0.78) and knowledge-related strategies (M = 3.85, SD = 0.81). Awareness-related strategies scored lowest but were also perceived as important (M = 3.70, SD = 0.74). Most individual strategies were similarly rated important (see Fig. 4): Respondents especially wished for improved interoperability (M = 4.38, SD = 0.81), continued technical support (M = 4.33, SD = 0.91), and improved usability (M = 4.20, SD = 0.88).

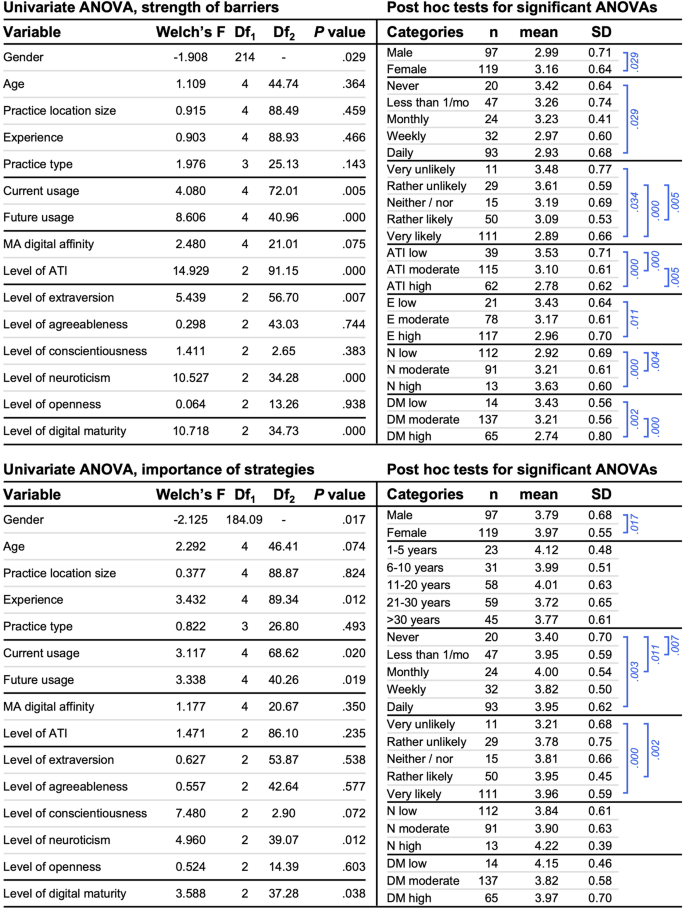

We conducted separate univariate ANOVAs and post hoc tests, to assess differences in the number and strength of adoption barriers and the number and importance of improvement strategies given the several inherent characteristics considered (see Fig. 5).

We found a similar pattern for the number of barriers, except that there was no difference between GPs based on gender (t(214) = −1.397, p = 0.082; t-test), yet a significant difference based on the perceived digital affinity of medical assistants (Welch’s F(4, 21.51) = 3.433, p = .003; Welch ANOVA). GPs who perceived their medical assistants to be somewhat not digitally affine (M = 13.60, SD = 5.13) reported significantly more adoption barriers adoption compared to respondents perceiving their medical assistants to be fully digitally affine (M = 9.42, SD = 5.87, p = 0.053, Cohen’s d = 0.77; Hochberg GT2 post hoc test).

In the next step, we conducted a linear hierarchical regression analysis to deepen our understanding of the association between adoption barriers, improvement strategies, and GPs’ inherent characteristics.

For the abstract and full-text screening, we excluded articles if they (1) were not related to digital health to maintain the focus on digital health and ensure the relevance for our research question; (2) did not address barriers or improvement strategies to digital health adoption or usage (i.e., focused on general attitudes, experiences, or the development or evaluation of digital health) to narrow the scope of our study; (3) were majorly focused on non-clinician populations (i.e., nurses or patients) as GPs hold a pivotal role in the digitalization of general practices and, thus, capturing their perspectives is of utmost importance; (4) were focused on care areas other than general practice as we believe that decision processes for adopting digital health solutions and subsequently implementing these essentially differ between different healthcare settings; and (5) were not original, peer-reviewed, published full-text articles to ensure the reliability and quality of the included literature. All inclusion and exclusion criteria used in this study were aligned in an expert panel before screening. Evidence from the included studies was synthesized by extracting and grouping potentially relevant barriers per a framework proposed in a recent review 11 and improvement strategies based on the underlying adoption process steps. Thus, we utilized recent research findings to cluster individual barriers and strategies more practically and broadly.

We aimed to validate the results of our literature review in qualitative expert interviews with GPs, ensuring the relevance and completeness of extracted barriers and improvement strategies to digital health adoption more broadly. Our expert interviews followed the COREQ checklist for qualitative research 65 (see Supplementary Table 4). We created a semi-structured interview guide based on the findings of our literature review to allow for flexibility yet achieve standardization of the interview procedure (see Supplementary Notes1 for the full interview questionnaire). The questions were designed to capture GPs’ concerns and wishes for digital health adoption as well as their assessment of the relevance of the proposed categories of barriers and strategies. Next to open-ended questions on perceived adoption barriers and relevant improvement strategies, we asked GPs to assess the relevance of the categories of barriers and strategies uncovered in the literature review, i.e., social, organizational, and technological barriers as well as development-related, awareness-related, knowledge-related, implementation-related, and policy-relates strategies. Four topics were covered in detail: (1) experience with digital health solutions, (2) indicators of digital maturity, (3) barriers to digital health adoption, and (4) relevant strategies to improve digital health adoption. This study specifically focuses on the latter two topics, while the first will be part of a separate analysis.

Participants were primarily recruited through targeted sampling and snowballing of personal contacts and colleagues. Participants received information about the research design and topics to be covered in the interview, including a definition of digital health solutions. Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the interview. The interviews were then conducted virtually in a one-on-one setting, videotaped, and transcribed verbatim to enable further qualitative analysis.

Data saturation was achieved after ten interviews. Participants were 53 years old on average, had been GPs for 18 years, and worked in cities of about 100,000 inhabitants. Four GPs had a solo practice, five worked in a group practice, and one practiced in a medical care center. Interviews lasted 45 min on average.

Coding and qualitative analysis were performed using MAXQDA 2022 67 . To enable a comparison with the findings of our literature review, we developed our coding scheme for our content analysis 68 deductively based on those findings. To gain further insights, we also inductively inferred themes from the interview material when multiple interviewees brought up the same topic. Based on that, we determined the number of interviewees that indicated the specific barriers or improvement strategy. These results were then compared to the findings of our literature review to develop items for our subsequent online survey. In the survey, we only included items for adoption barriers or improvement strategies proposed by more than four articles or mentioned by more than one interviewee to ensure theoretical and expert consensus.

We next conducted a cross-sectional survey investigating perceived adoption barriers, relevant improvement strategies, and inherent characteristics of GPs. The survey adhered to the CHERRIES checklist for internet surveys 66 (see Supplementary Table 5 for the completed CHERRIES; see Supplementary Notes2 for a translated version of the survey questionnaire). The survey was divided into six sections: (1) demographics, practice-related characteristics, and digital health usage, (2) GPs’ affinity for technology interaction, (3) Big Five personality traits, (4) digital maturity of the practice, (5) perceived adoption barriers, and (6) relevant improvement strategies. This paper focuses on the findings of sections 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6, as we aimed to investigate the influence of GPs’ inherent characteristics on barriers and improvement strategies. The findings concerning digital maturity were covered in detail in another analysis 69 . Participants were informed of the research objectives, target population, length, and IRB approval on an introductory page. Information regarding data storage and security and the researchers involved were provided on the following page. Before continuing with the survey, participants had to provide informed consent. Afterwards, participants were given a definition of relevant concepts covered in the survey, i.e., digital maturity and digital health solutions.

We captured participants’ demographics and practice-related characteristics using single-choice questions. The current and expected future usage of digital health solutions, as well as the perceived digital affinity of medical assistants were assessed using 5-point Likert-type scales.

To measure GPs’ affinity for technology interaction, we used an established 9-item 6-point Likert-type scale 45 that captures a person’s tendency to actively participate in intense technology interaction. Using a 21-item German-language measure 46 , we evaluated GPs’ personality traits. The 5-point Likert-type scale evaluates the Big Five personality traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness. Digital maturity was assessed using 28 items with a 5-point Likert-type scale developed in line with a recent systematic review 57 .

We developed the 26 items to assess adoption barriers based on the synthesis of our literature review and expert interview results. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the items across technological, social, and organizational barriers on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Similarly, the 23 items for our assessment of improvement strategies were also developed based on previous results and captured using a 5-point Likert-type scale. Improvement strategies assessed covered development-related, awareness-related, knowledge-related, implementation-related, and policy-related strategies.

We pretested the survey questionnaire with 15 physicians working in ambulatory care settings to ensure clarity, comprehensiveness, usability, and technical functionality. Question wording and the introductory page were refined after the pre-test. The survey was then conducted between April and mid-August 2023 and took about 10 to 15 min to complete. Various recruitment channels were used to reach a broad sample of German GPs. These included interview participants, personal contacts, teaching practices, physician networks, research practice networks, and GP mailing lists. Participants were contacted via mail using publicly available mail addresses. As we conducted the survey in an open-access mode, anyone with an access link could participate, and we could not track which invited participants had started or completed the survey. We further did not provide incentives for participation.

We thoroughly cleaned the data obtained before performing statistical analyses (see Fig. 7). Following standard practice 70 , our data cleaning included removing responses without informed consent, incomplete responses, and duplicate responses. In the next step, we also removed responses that took very little time to complete 71 and those that displayed careless answer behavior over several survey pages 71 . We further eliminated any responses that did not adhere to our anonymity criterion to comply with data privacy. In total, 216 responses from the 373 people who initially clicked on the survey link are included in our analysis.

For our statistical analyses, we first computed the mean value for respondents’ affinity for technology interaction, their personality traits, their digital maturity, the three categories of adoption barriers, and the five categories of improvement strategies. To allow for an analysis of the influence of GPs’ inherent characteristics on barriers and improvement strategies, we further computed two overall outcome measures for both variables: One outcome measure represents the number of barriers (strategies) and was calculated as the sum of barriers (strategies) that received a score of 4 or higher on our 5-point Likert-type scale and were thus perceived as such. The second outcome measure was calculated as the average across barriers (strategies) and represents the perceived strength of barriers (the perceived importance of strategies). SPSS version 29.0 for Macintosh 72 was used for all statistical analyses.

We assessed the internal consistencies of the scale used using Cronbach’s Alpha 73 (see Table 3). Most internal consistencies can be considered as acceptable or good and are in line with previous research 45,46 . However, the internal consistency for conscientiousness was lower in our sample compared to the original study 46 , which might be due to the overall high conscientiousness and low variability of the score in our sample.

Table 3 Sample size, mean, standard deviation, number of items, and internal consistencies of the scales used

We conducted a linear hierarchical regression analysis to deepen our understanding of the association between barriers and strategies and the independent variables, further accounting for the continuity associated with personality and digital affinity-related variables. We chose a hierarchical approach for entering variables into our model to determine the influence of demographic and practice-related variables on barriers and strategies and to separate this from the influence of digital health usage, digital affinity, and personality. Potential multicollinearity of predictors was assessed following practical recommendations using VIF and tolerance values 75 . As all VIF values were below ten and tolerance values greater than 0.1, multicollinearity does not seem to flaw our analysis. In our sequential approach, the first stage incorporated demographics and practice-related characteristics, including gender, age, practice location size, professional experience, and practice type. The second stage introduced variables related to digital health usage – current and expected future usage. The third stage added digital affinity-related variables, encompassing the perceived digital affinity of medical assistants and GPs affinity for technology interaction. The fourth stage introduced the Big Five personality traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness. In the final model, the digital maturity of the practice was included. This sequence followed prior research and theoretical reasoning, with variables analyzed in past research entering earlier in the model. In addition, the distinct blocks analyzed covered different categories of inherent variables, namely demographics, practice-related characteristics, digital health usage, digital affinity, and personality. As our analysis of the relationship between perceived barriers and strategies and inherent characteristics was novice, our analysis focused on main effects of individual predictor variables and explicitly refrained from analyzing and interpreting interaction effects.

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.